A brighter future begins now! Apply today for Fall 2025!

A brighter future begins now! Apply today for Fall 2025!

Opinion: The real work of equity and inclusion is difficult, messy and absolutely necessary

Recy Dunn

July 29, 2024

Leaders have been lied to for decades about DEIA. We’ve been told there is a clean, clear way to integrate diversity, equity, inclusion and anti-racism into an organization and that simply making a statement, changing hiring demographics by a percentage point or investing in training is enough.

All of those things are positive; all are progress. However, human beings aren’t data points that can easily be changed and manipulated. We’re complex individuals with many layers and connecting identities. The equity we are hoping to see will not be reached by easy-to-achieve metrics alone.

That’s why we must push ourselves and our organizations to lead our DEIA work by accepting the mixed and unique nature of all our identities, so we can better serve our students, staff and families.

This sounds incredibly messy because it is.

The oppressive structure of systemic racism in this country is powerful, poisonous and must be explicitly combatted. Anti-racism must remain a core part of our DEIA work. We must talk about the hard things.

As a Black man and leader in public education, I have grappled with the complexities of race and identity throughout my life. My entry into this topic was — and largely still is — grounded in my racial identity and my upbringing in Texas, something I’m reminded of every time I look at my birth certificate and see the word “Negro” on it.

Yet we are all more than our race. It’s all too easy to focus solely on the parts of who we are that are the most visible or important to us. I am Black, I am a cisgendered man, I am heterosexual, I am Texan, I am a father and so much more.

Inclusion and belonging work is more than race too. In addition to grappling with our own personal DEIA journeys, we must navigate the surrounding political environments of our schools. These contexts often lead teachers and leaders to cherry-pick aspects of DEIA that seem easier to address, or more palatable, while neglecting others.

For example, many teachers struggle to tell parents about books and materials that feature religious or sexual identities. Yet these same teachers find it easy to vocalize the needs of students with learning disabilities.

Schools nationwide celebrate Black History Month enthusiastically, yet voice concerns about whether Pride Month should be recognized. Staff members urge schools to prioritize hiring diverse educators, yet advocate against using school budgets to update school facilities for all bodies.

With such messy work, it’s natural to cling to what feels most achievable or comfortable. Educators are overwhelmed by challenges, from the pandemic’s impact on learning to resource gaps, safety concerns and a myriad of society’s ills.

Facing down systemic racism can feel impossible, as can dismantling overlapping systems of oppression. When we see DEIA as a singular objective to achieve or a single battle to win, we can feel defeated.

But when educators adopt DEIA as a mindset and approach, that discipline allows us to make slow but steady progress toward a more just future. This is forever, all-encompassing work. The growth and progress for each of us is never done and requires us to lean into productive struggle.

To make real gains in creating inclusive schools, we need to go beyond just meeting goals and instead commit to making sometimes difficult choices and confronting uncomfortable truths to create a new world of standards. As we approach decisions, we must ask ourselves not only what measurable outcomes our choices will achieve, but also how they will change our culture. Just as systemic racism is entrenched in American culture, we need to entrench DEIA in the work of schools.

Does that sound hard? Yes.

At the charter network I lead, DEIA is everyone’s responsibility. This commitment is rooted as much in mindset as it is in accountability. It’s the lens we use to critically examine our systems, policies, programs and interactions as we aim to eliminate inequitable and exclusionary practices — without focusing solely on one identity, but instead considering how different identities interact with one another.

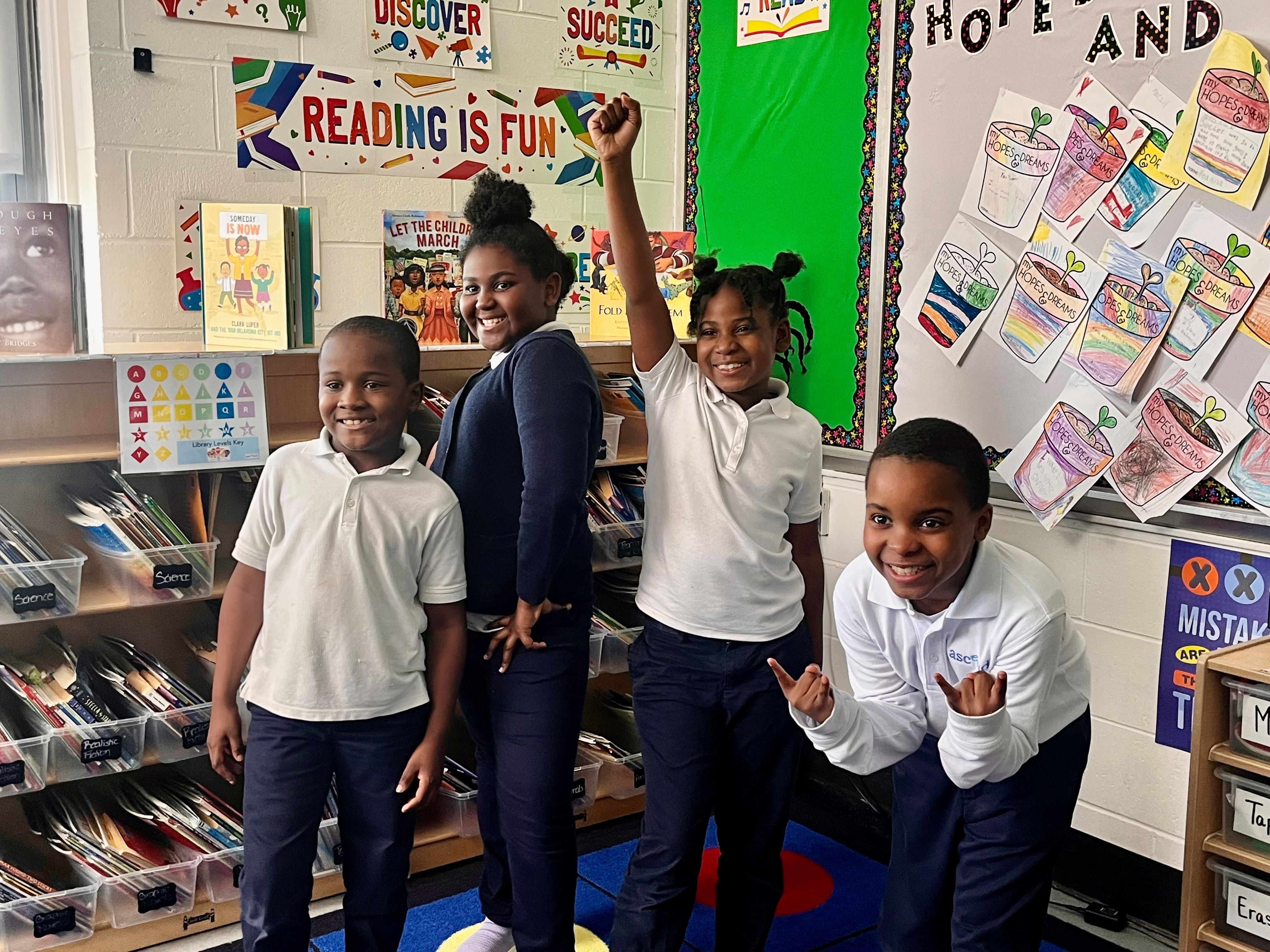

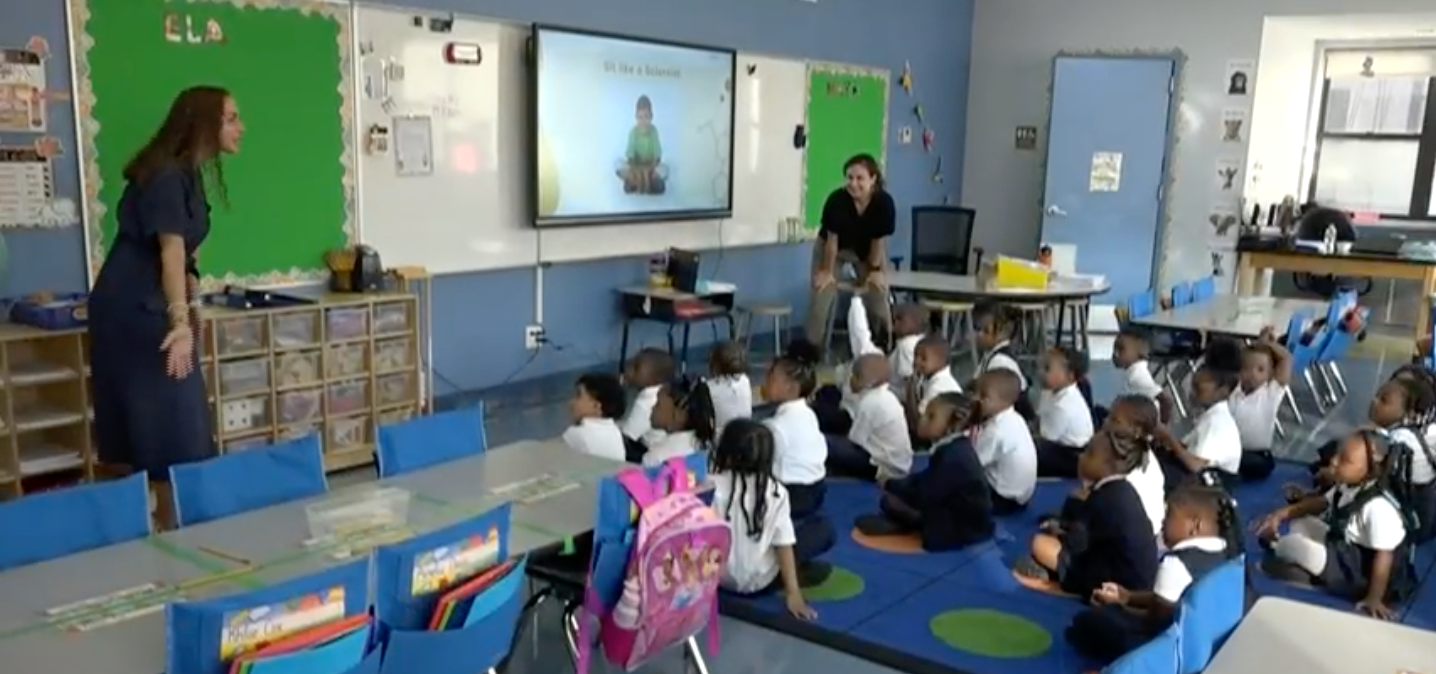

In the classroom, we introduced reading programs that acknowledge literacy as a key factor in creating an anti-racist education; our literacy efforts are complemented by classroom library selections for all grades that promote an inclusive learning environment for students of all identities.

We see the work as both immediate and ongoing. We name and embrace that complexity. More than 79 percent of our staff do not identify as white; 64 percent identify as Black. The majority of our school leaders and executive team reflect a similar mix of identities. Every staff member is required to engage deeply with our value of centering justice.

We’re actively working to increase religious and gender inclusion, such as with designated prayer spaces and more all-gender bathrooms, so students feel supported every time they enter our buildings.

Much more work remains to be done. We will hold ourselves to it and continue to move forward, and I remain hopeful that we’re moving in the right direction.

It’s time for all of us to dive into the mess.

Recy Benjamin Dunn is CEO of Ascend Public Charter Schools, a network of K-12 public charter schools serving nearly 6,000 students in 17 schools across Brooklyn.

This story about DEIA work was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s weekly newsletter.

Share

Other Articles

© Ascend Public Charter Schools 2025