A brighter future begins now! Apply today for Fall 2025!

A brighter future begins now! Apply today for Fall 2025!

Building a high school that bridges inequity in Brownsville, Brooklyn

Steven F. Wilson

April 18, 2016

This opinion piece appeared in The Hechinger Report on December 10, 2015.

In her affecting three-part account of the launch of our first charter high school in Brownsville, one of the most challenged communities in New York City, The Hechinger Report’s Sara Neufeld asks: Can a liberal arts education fused with a supportive culture equip students—in a way that has proved so difficult for other urban academic initiatives—with the knowledge, confidence, and character to thrive in college and beyond?

As Neufeld notes, the dominant No Excuses model of urban charter schools has posted high test scores. But critics charge that many students leave, finding the schools joyless and unforgiving, and that in some schools, difficult to educate students are actively counseled out. College persistence rates have disappointed.

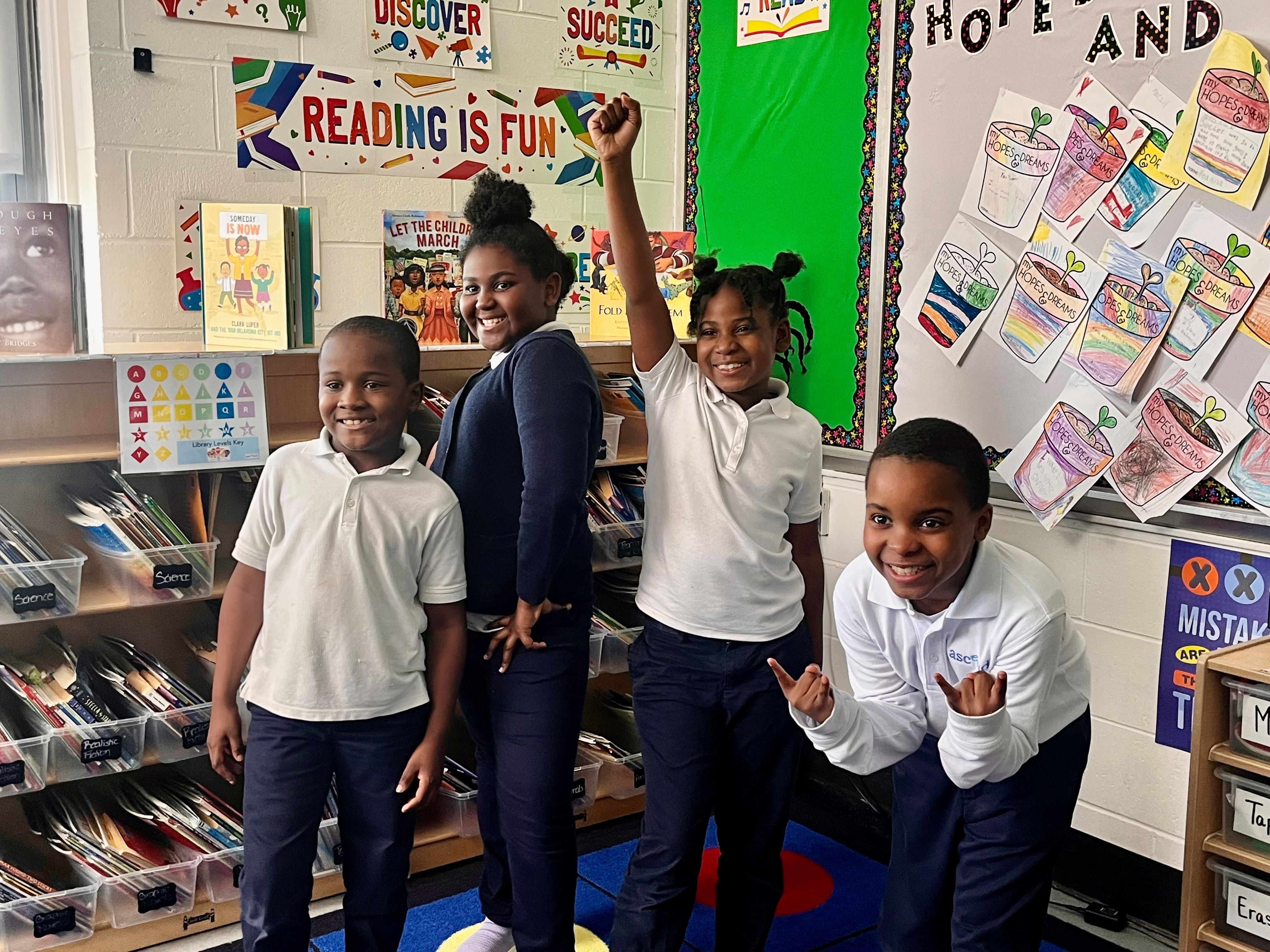

At our new high school, one of nine charter schools we operate in central Brooklyn together enrolling some 3,500 students, we aim to demonstrate an alternative model: a rich and vibrant liberal arts education in a warm and supportive setting that will benefit underserved communities. Our schools can be scaled without limit, as they do not rely on the largesse of wealthy donors—resources that are not widely available.

“I’ve never felt inspired before,” Jann Peña, an entering ninth grader at our new high school, tells Neufeld. He knows he should push himself harder, she writes, but hasn’t seen the point. Coming from an impersonal, academically undistinguished middle school of 900 students, he could hardly be expected to feel otherwise.

The liberal education offered Jann at Ascend has the capacity to inspire him and students of every background. We reject as condescending and ineffective the widespread approach of first appealing to students’ interests in their immediate surroundings, and only from there, expanding to the broader world.

All children, we find, are inspired and uplifted by the greatest works of imagination from across ages and cultures. That is why our fifth graders study the timeless myth of Icarus and Daedalus, examine in the school’s gallery Breughel’s exquisite painting of Icarus’s fall into the sea, and undertake a close reading of Auden’s famous 1938 poem, “Musée des Beaux Arts,” which was inspired by Breughel’s painting. In the spring, and every year thereafter, they read and perform Shakespeare. Our students read Dubois’s critique of Booker T. Washington, and the great literary works of Frederick Douglass, Langston Hughes, and Edwidge Danticat.

For students to develop intellectual passions—so necessary for entrance into and success in selective admission colleges—they must be exposed to adults who themselves exhibit passions and encourage students to discover their own.

If every student falls in love with something—from computer coding to poetry, from calculus to philosophy—it will be the school’s greatest triumph. That is why vivacious, intellectually alive teachers like the school’s Taylor Delhagen, whom Neufeld profiles, are indispensable.

A liberal education, we believe, liberates. It prizes critical thinking and questioning, celebrates—and yet challenges—the literary canon, encompasses music and the arts, cultivates moral judgment and civic responsibility, endows our students with the incomparable advantages of clear thought, confident voice, and a love for the written word and the beauty of math and science. It rouses imagination and creativity, opens hearts and minds, and inspires understanding of oneself and of others. It galvanizes responsible and generous participation in a diverse and complex society. It teaches our students to think for themselves and offers them options to, as Neufeld states, “shape a different destiny.”

In the stories’ most poignant interview, Melissa Jarvis-Cedeño, the school’s extraordinary and experienced director, tells Neufeld of her own son, Josef, who became ensnared in the criminal justice system. She says that having never been taught “to think for himself … it was all too easy for him to be lured into a gang.” She is committed to offering her students the education her son failed to receive.

Some may question the practicality, in a brutal job market, of such an education. Isn’t it a luxury for the entitled? No, as it turns out. A survey by the Association of American Colleges and Universities found that 80 percent of employers believe that college students should obtain, regardless of their major, a foundation in the liberal arts and sciences. Furthermore, in our rapidly changing world, we might prepare our students for one job today only to find that it has disappeared tomorrow. Far better to prepare students with the general capacities, prized in any era, that will allow them to adapt to whatever the future brings.

But our liberal arts curriculum is not enough. We must also create a warm and supportive school culture dedicated not solely to building the often cited “grit,” but one that fosters what we call agency—students’ belief that they are in control of their own lives and can act of their own free choices. This will prove essential for college life, where freedom and responsibility will be exercised in a nearly complete absence of supervision. If all that students have experienced in No Excuses schools is abundant structure and little autonomy, is it any wonder they flounder in college?

Taylor Delhagen tells Neufeld that he and his colleagues left his former school because, while they were successful at producing high test scores, they “felt stifled” in what they see as the greater task: “developing human beings” and serving all students. At his old school, “he saw low-performing students counseled out.��” That is why, as Neufeld describes, Ascend schools depart from a punitive and proscriptive disciplinary model with associated high rates of referrals and suspensions.

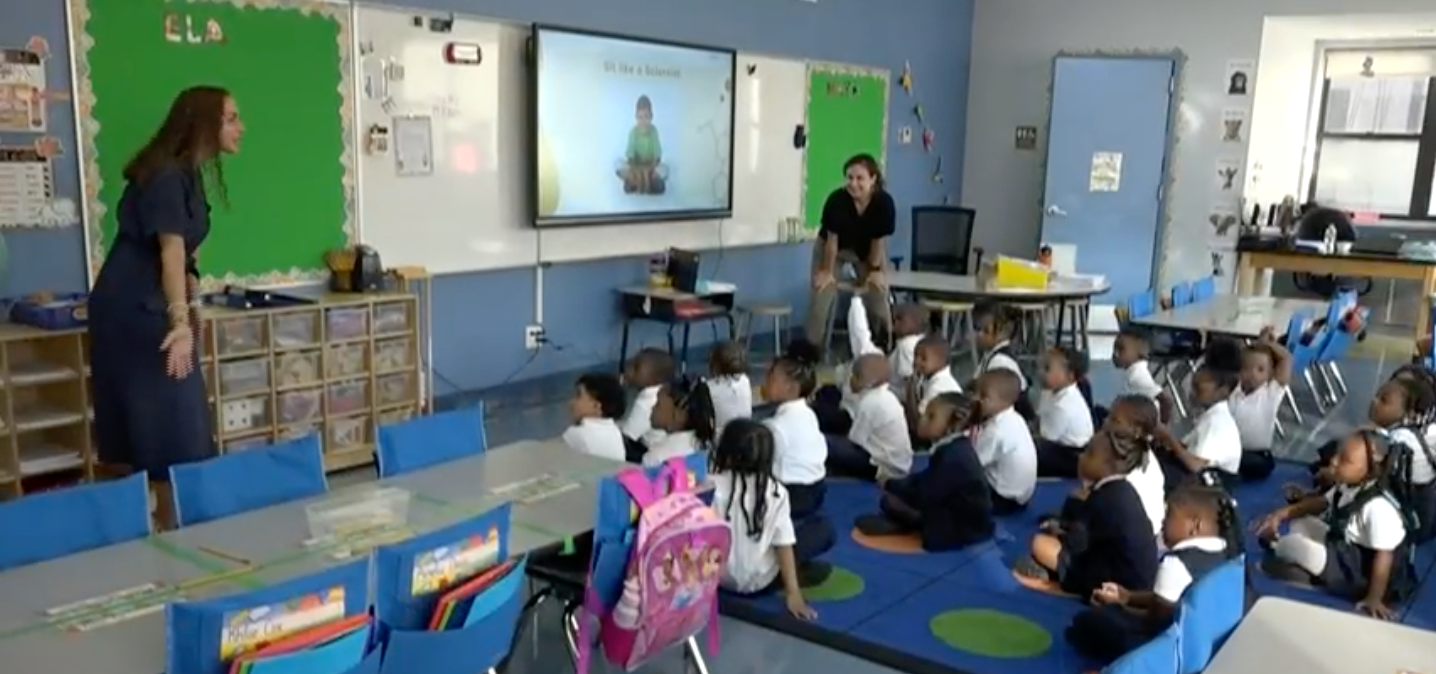

In the lower schools, joyful classroom communities nurture students’ sense of belonging, and foster children’s social and emotional competencies. Positive language replaces warnings and threats, and students learn empathy, collaborative problem-solving, and self-control. The scaffolding of the early years is gradually pulled away so that by the time they reach college, students can self-manage with full autonomy. In high school, restorative practice empowers students to resolve conflicts on their own, gain an understanding of the impact of their actions, and take responsibility for their choices.

At Ascend, our mission insists that our schools be truly public institutions: free and open to all children, without admission criteria, tuition, or fees. We don’t counsel out challenging students, we fill all vacated seats through grade 9, and we proudly serve students with special needs and limited English proficiency.

Each spring at our schools we administer the TerraNova, a nationally normed test of student achievement. Ascend students arrive performing, on average, in the bottom quartile of performance in both reading and math and rise, consistently across schools, to the third quartile, where they stay as they move up the grades. By this measure, we are beginning to rectify the educational effects of disadvantage.

It is early to assess the success of Brooklyn Ascend High School, but we are confident of our model’s promise.

Please send comments or questions to blog@ascendcharterschools.org.

Photo credit: Julienne Schaer

Share

Other Articles

© Ascend Public Charter Schools 2025